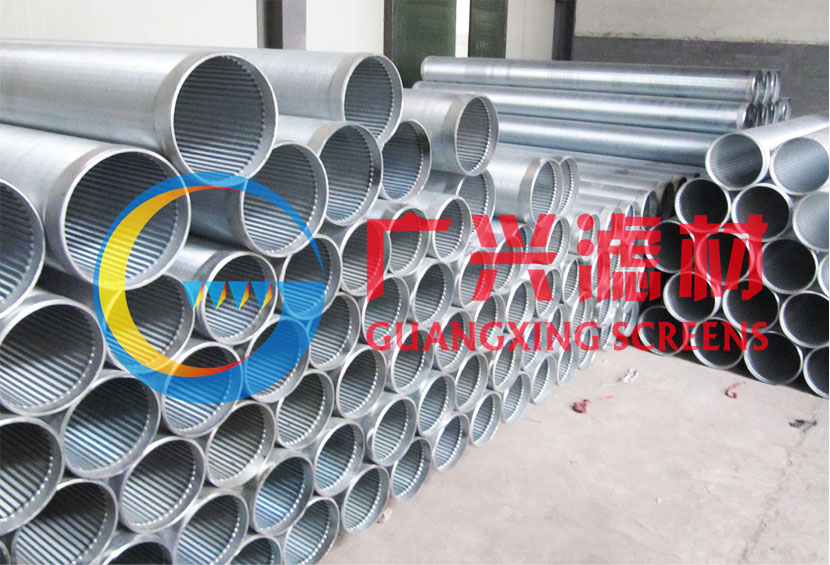

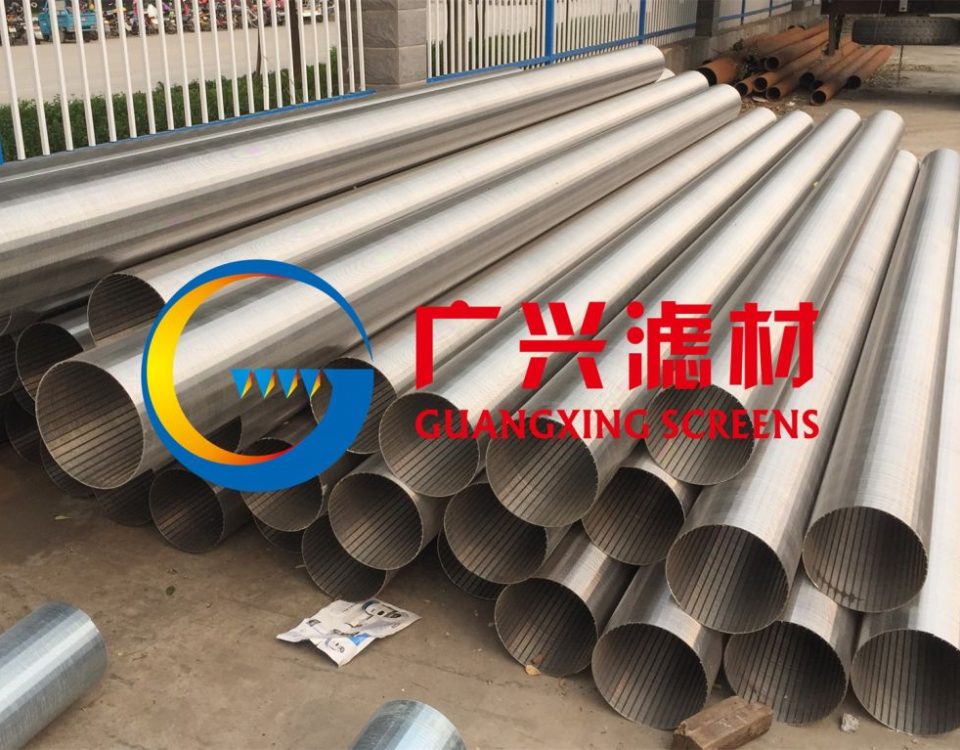

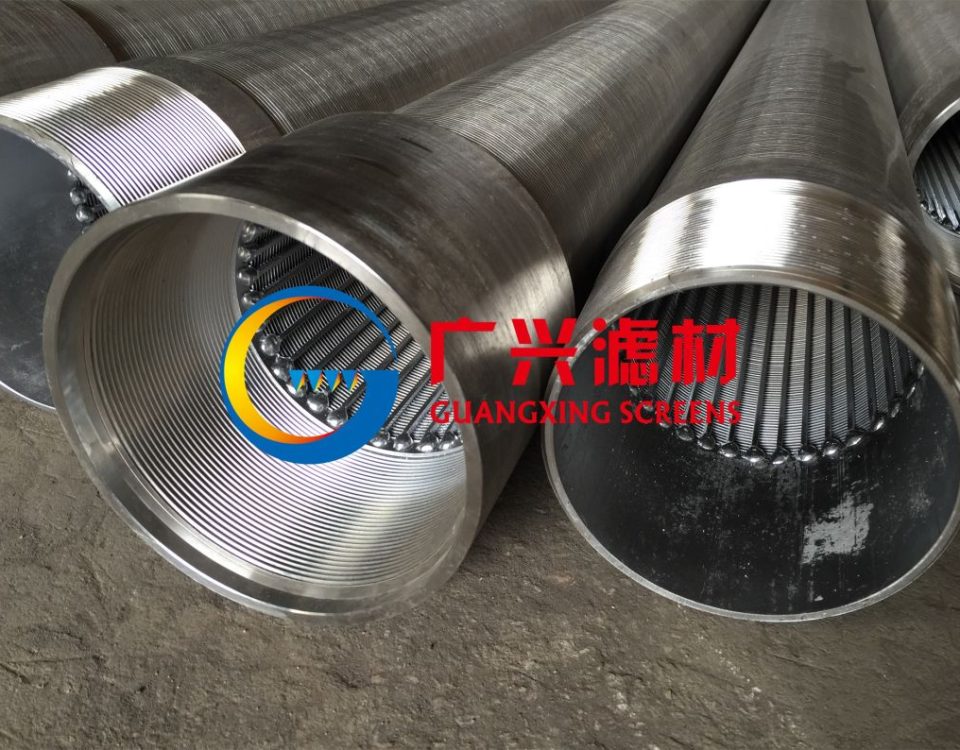

Gravel Pack Screen for Water Sand-Control

August 10, 2025

Stainless Steel Well Screens Manufacturing Processes

September 9, 2025The Profound Influence of Manufacturing Processes on the Microstructure and Performance of Stainless Steel Well Screens

The specification of a stainless steel alloy for a well screen, such as the ubiquitous 304 or 316L, or the more robust duplex 2205, establishes a foundational chemical blueprint that suggests a certain range of performance characteristics, notably its inherent potential for corrosion resistance. However, this nominal composition is merely the starting point of a complex metallurgical journey; the ultimate mechanical properties, corrosion behavior, and long-term durability of the finished screen are overwhelmingly dictated by the specific manufacturing processes it undergoes. Each stage of transformation, from the initial melting of raw elements to the final precision machining of slot patterns, imparts profound and often irreversible changes to the material’s internal architecture—its microstructure. This intricate relationship, encapsulated in the fundamental materials science paradigm of “Processing → Structure → Properties,” means that two screens made from the same ASTM-grade alloy can exhibit wildly different performance profiles in the field based solely on their fabrication history. A deeply cold-worked, punch-cut screen is microstructurally a different entity altogether from a solution-annealed, laser-cut, and electropolished one. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of how processes like hot working, cold working, welding, heat treatment, and cutting technologies alter the grain structure, dislocation density, phase stability, and surface chemistry is absolutely critical for engineers and hydrogeologists to make informed decisions, predict service life, and mitigate the risks of catastrophic failure in demanding downhole environments.

The journey of microstructural evolution begins not with the screen fabricator but at the mill where the raw material is produced. The melting process, typically conducted in an Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) followed by precise refinement in an Argon Oxygen Decarburization (AOD) vessel, is designed to achieve the precise chemical cocktail and, crucially, to scavenge impurities and lower carbon content to acceptable levels, especially for the “L” grades prized for their weldability. The subsequent continuous casting of this molten alloy into slabs or billets initiates the first critical structural formation: a coarse, dendritic microstructure characterized by significant chemical segregation, where alloying elements like chromium and molybdenum are not uniformly distributed but are concentrated in the inter-dendritic regions, creating microscopic heterogeneities that represent potential weak points for corrosion initiation and mechanical failure if left unaddressed. This cast structure is wholly unsuitable for a high-performance component; it possesses lower strength, inferior toughness, and unpredictable behavior under stress. Consequently, the first major microstructural overhaul occurs through hot working, where the cast billet is reheated into the austenitic stability zone (above 1000°C for austenitic grades) and subjected to controlled deformation through processes like hot rolling or forging. This high-temperature mechanical working facilitates dynamic recrystallization, a powerful mechanism wherein the coarse, brittle cast grains are broken down and replaced by a new generation of fine, equiaxed grains, simultaneously homogenizing the chemical distribution and eradicating the dendritic segregation, thereby laying the groundwork for a material that is stronger, tougher, and more predictably corrosion-resistant due to a more uniform potential for passive film formation.

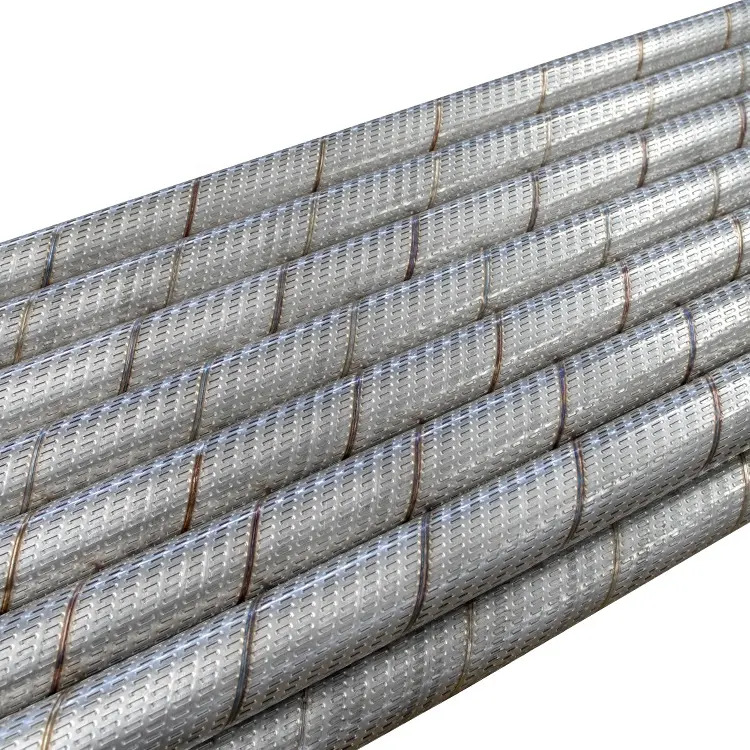

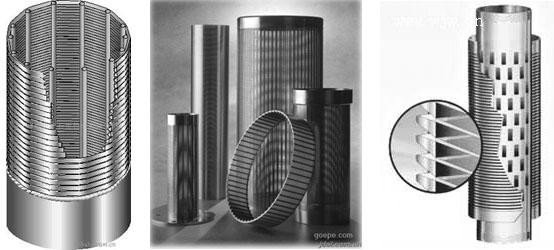

Following hot working, the material is further processed into the forms required for screen fabrication: primarily seamless pipe for slotted screens and drawn wire for wire-wrap screens. The manufacture of seamless pipe, often via the Mannesmann plug mill process, involves piercing a hot billet and elongating it through a series of rolls; this constitutes further hot working, further refining the grain structure and enhancing the directional properties of the material. The pipe may then be solution annealed—heated to a temperature where all carbides are dissolved into solid solution and then rapidly quenched to freeze this homogeneous state—resulting in a soft, ductile, and corrosion-optimized microstructure. Alternatively, for welded pipe, a cold-rolled strip is formed and its edges fused together, creating a continuous weld seam that introduces a critical microstructurally distinct region: the Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ). Within this HAZ, the base metal’s microstructure is altered by the thermal cycle, risking phenomena like sensitization (chromium carbide precipitation at grain boundaries in specific temperature ranges) and grain growth, which can severely compromise local corrosion resistance and mechanical properties, making the weld seam a potential Achilles’ heel unless properly addressed with subsequent heat treatment or the use of stabilised grades. For wire-wrap screens, the rod is subjected to severe cold drawing, a process that involves pulling the material through a series of progressively smaller dies, which massively increases dislocation density, dramatically elongates the grains in the drawing direction, and introduces substantial residual stresses, resulting in a wire that is immensely strong but also anisotropic and lacking in ductility, a trade-off that must be carefully managed.

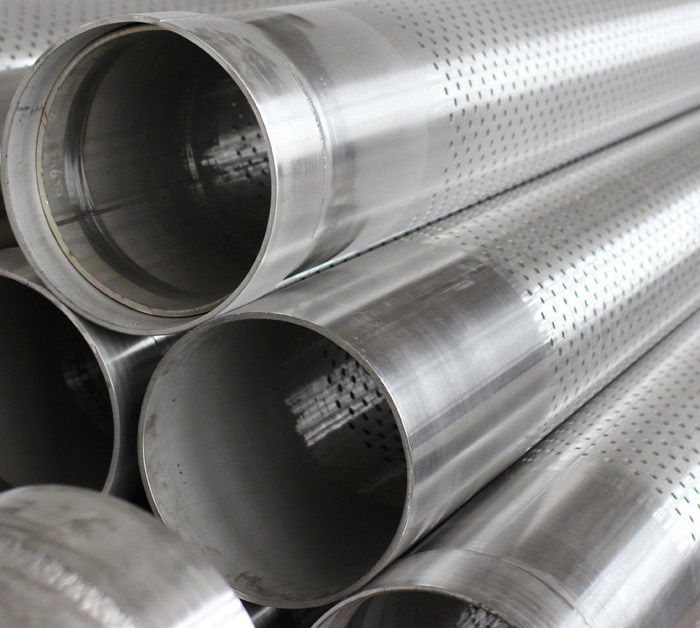

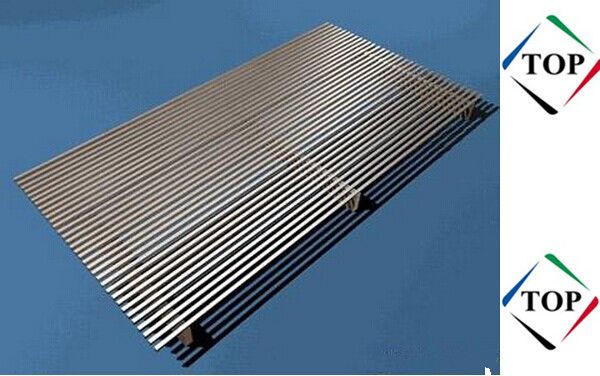

The most transformative stage for the microstructure occurs during the actual screen fabrication processes, where the base pipe or wire is converted into a functional filter. The method of creating the slots is particularly impactful. Punching or stamping, a common and cost-effective method, is an extreme form of cold working localized to the slot perimeter. The shearing and deformation action creates a severely work-hardened zone with an astronomically high dislocation density, plastically deformed grain boundaries, and a characteristic profile of residual stresses—often compressive at the very surface but with tensile stresses lurking just beneath. This microstructural upheaval has direct performance consequences: while the slot edges become very hard and abrasion-resistant, the stressed, disrupted, and often micro-cracked surface provides ideal nucleation sites for pitting and crevice corrosion, and the combination of this damaged microstructure with the geometric stress concentration of the slot itself significantly reduces the fatigue strength, making the screen more vulnerable to failure under cyclic loading from pump operation or water hammer. In contrast, laser cutting, a high-precision thermal process, vaporizes material to form the slot, creating a entirely different microstructural alteration: a Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ) along the cut edge, complete with a fusion zone of re-solidified dendritic material, a region susceptible to sensitization and grain growth, and an often-overlooked heat tint—a thick, non-protective, chromium-depleted oxide scale that is catastrophically vulnerable to corrosion, necessitating mandatory post-cut pickling and passivation to restore integrity.

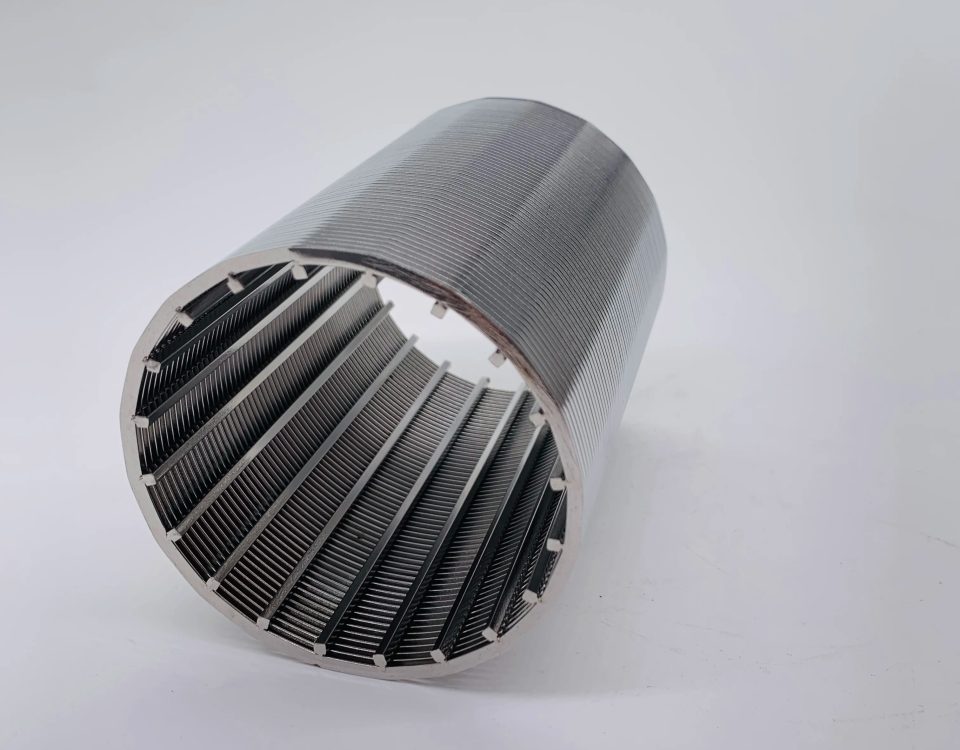

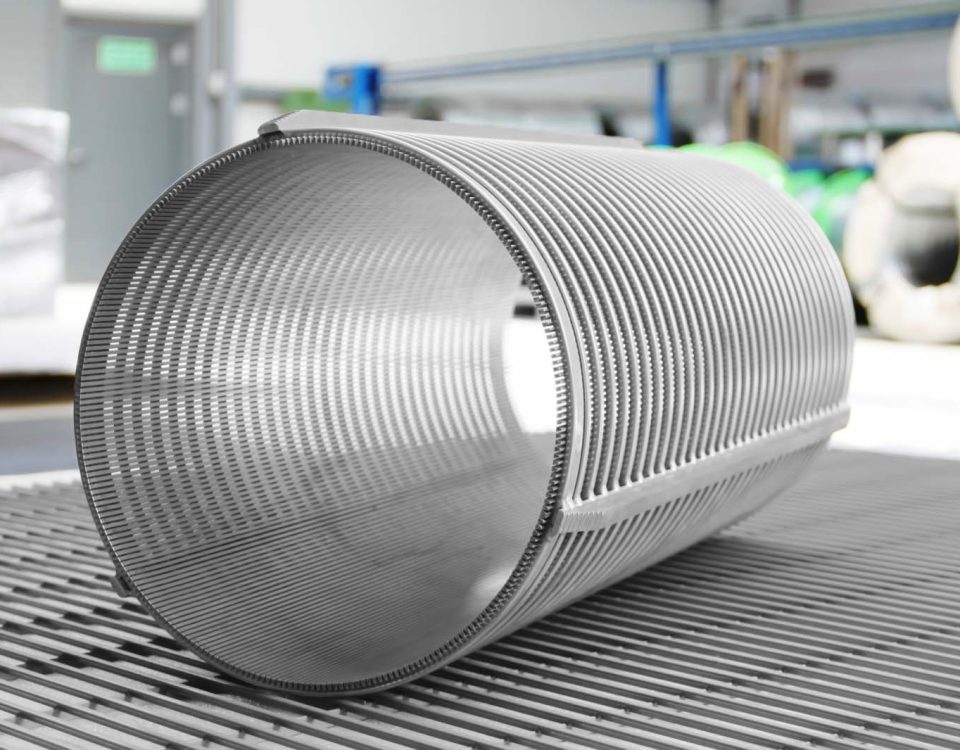

Abrasive waterjet cutting presents a third pathway, a cold-cutting process that erodes material with a high-pressure stream of water and abrasive garnet, introducing negligible heat input and thus avoiding the formation of a HAZ, phase transformations, or thermal distortions, thereby preserving the base metal’s microstructure right up to the cut edge; however, the resulting matte and microscopically rough surface, while free of thermal damage, can still act as a site for particle adhesion and crevice initiation, often requiring subsequent passivation or electropolishing for optimal performance. For wire-wrap screens, the fabrication process involves helically wrapping the cold-drawn wire around a support structure and welding it at each contact point; each of these thousands of microscopic welds creates its own fusion zone and HAZ, presenting a distributed corrosion risk across the entire screen surface that demands rigorous quality control in welding and a comprehensive post-fabrication cleaning and passivation regimen to ensure the longevity of the assembly and prevent unraveling due to localized corrosive attack at a weld nugget.

Finishing processes represent the final opportunity to engineer the microstructure and surface state for optimal performance. Heat treatment, particularly full solution annealing and quenching, is a radical reset button: it dissolves precipitated carbides, eliminates all cold work, recrystallizes a new fine, equiaxed grain structure, and annihilates residual stresses, resulting in a microstructure that delivers maximum corrosion resistance and ductility; however, this comes at the absolute expense of mechanical strength, rendering the screen susceptible to collapse under lower pressures, a trade-off that often dictates that annealing must be performed before any cold-forming if high collapse strength is required. A lower-temperature stress relief heat treatment offers a compromise, reducing detrimental residual stresses to mitigate the risk of stress corrosion cracking (SCC) without significantly altering the strength gained from valuable cold work. Beyond thermal treatments, chemical and electrochemical finishing steps are paramount. Pickling, using a nitric-hydrofluoric acid mixture, is non-negotiable after any thermal process to surgically remove the chromium-depleted layer and heat tint, while passivation, in a nitric or citric acid bath, promotes the growth of a new, continuous, and protective chromium oxide passive film. Electropolishing, the pinnacle of surface treatment, electrochemically smoothes the surface, removing the work-hardened layer, micro-peaks, and embedded contaminants, simultaneously enhancing corrosion resistance by increasing surface chromium content and providing a ultra-smooth finish that minimizes bacterial adhesion and simplifies well rehabilitation, representing a significant upgrade in performance for critical applications.

In synthesis, the manufacturing pathway chosen by a fabricator creates a final product with a specific microstructural signature that dictates its performance profile. A pathway prioritizing high collapse strength will embrace severe cold working through processes like pipe cold-drawing and punch slotting, resulting in a microstructure defined by high dislocation density, elongated grains, and significant residual stresses, yielding superb mechanical properties but accepting a compromised, more vulnerable corrosion performance that must be managed through environmental controls and perhaps protective coatings. Conversely, a pathway prioritizing maximum corrosion resistance will employ a full solution anneal followed by heat-free cutting methods like waterjetting or meticulously cleaned laser cutting, culminating in a recrystallized, equiaxed, stress-free, and homogeneous microstructure with a pristine surface, offering unparalleled resistance to pitting, crevice corrosion, and SCC, but relying on increased wall thickness to compensate for its lower inherent yield strength. Therefore, specifying a well screen must transcend a simple selection of alloy and slot size; it necessitates a technical dialogue with manufacturers about their specific processing sequence—how the base pipe is produced, how slots are formed, and what heat treatments and cleaning steps are applied—to ensure the manufactured microstructure is precisely aligned with the chemical, mechanical, and biological challenges of its intended downhole mission, ensuring reliability and longevity through informed metallurgical choices.