Why is the V-shaped wire profile superior to traditional bridge slot or perforated pipes for sand control?

December 27, 2025

Microscopic Erosion-Corrosion Mechanism of Woven Metal Mesh in Sand-Control Screens

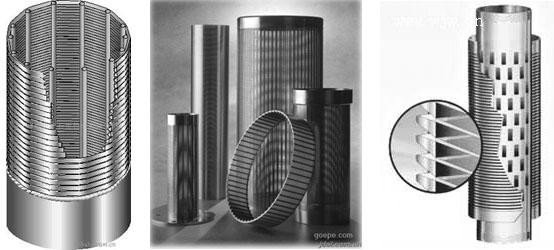

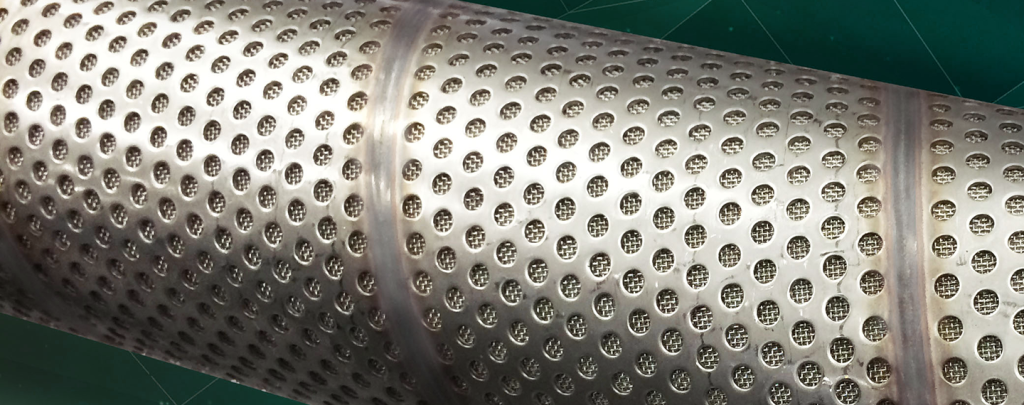

January 11, 2026The conceptualization of the degradation of metal wire mesh filters within sand control screens necessitates a departure from macroscopic structural observations toward a more granular, microscopic interrogation of the synergistic relationship between particle bridging, fluid-structure interaction, and the localized kinetic energy of entrained solids. To begin this inner monologue on the failure of such intricate systems, one must first envision the screen not as a static barrier but as a dynamic, evolving boundary layer where the physics of filtration and the mechanics of destruction are inextricably linked. The metal wire mesh, often composed of austenitic stainless steels or high-nickel alloys like 316L or Alloy 20, is woven into precise architectures—such as the Plain Dutch Weave (PDW) or the Twill Dutch Weave (TDW)—to create a tortuous path for fluid while excluding formation sands. However, the very precision of this weave becomes its undoing when the equilibrium of the reservoir is disturbed. As fluid begins its migration from the formation into the wellbore, it carries with it a spectrum of particulate matter, from fine silts to larger quartz grains, whose interaction with the pore throats of the mesh initiates a cascade of events that ultimately leads to the catastrophic failure of the screen’s integrity. The plugging phase is not merely a mechanical blockage but a complex process of bridge formation where the ratio of particle size to pore size (d/D) dictates the stability of the occlusion. When multiple particles converge upon a single pore throat, they form a “keystone” bridge, a stable arch-like structure that effectively reduces the flow area. This reduction in area is the critical inflection point in the screen’s lifecycle because it triggers a shift in the local hydrodynamic regime; according to the principle of continuity, as the cross-sectional area of the flow path diminishes due to plugging, the local fluid velocity must increase proportionally to maintain the volumetric flow rate. This “nozzle effect” transforms a relatively benign, low-velocity laminar flow into a high-velocity jetting action, where the fluid, now laden with abrasive particles, is directed with pinpoint accuracy against the microscopic surfaces of the metallic wires.

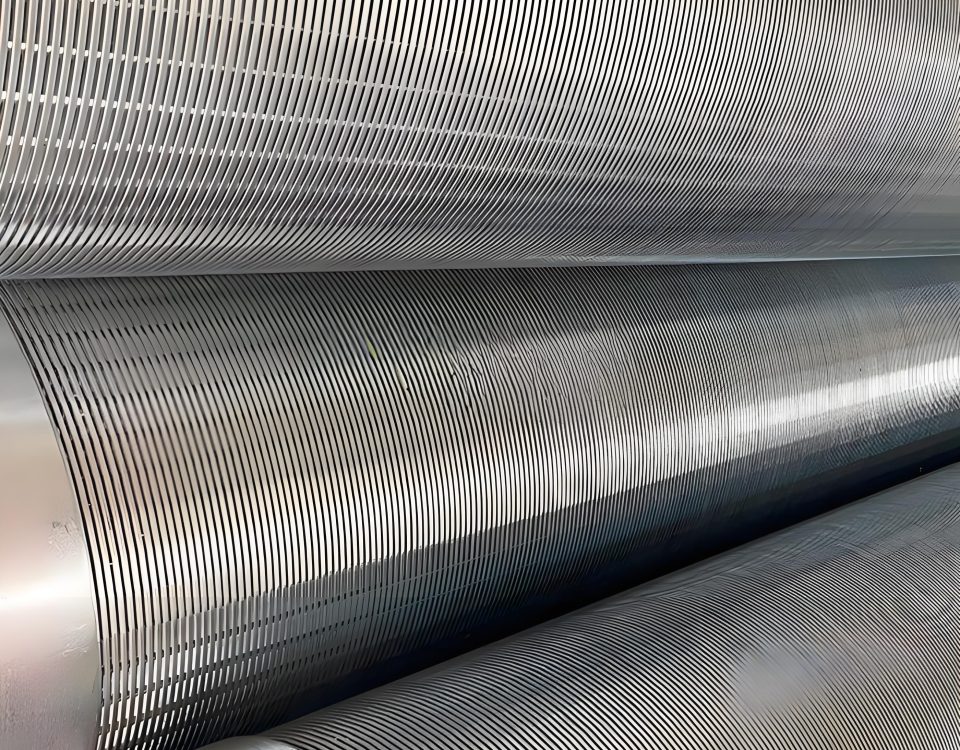

This transition from plugging to erosion is the fundamental mechanism of “plugging-erosion damage,” a phenomenon where the blockage itself creates the conditions for the subsequent destruction of the filter medium. To analyze the microscopic damage, one must consider the metallurgical response of the wire to repeated solid particle impacts. The erosion of metallic materials by solid particles is typically categorized into cutting wear at shallow impact angles and deformation wear at high impact angles. In the context of a partially plugged wire mesh, the trajectories of the particles are chaotic and dictated by the turbulent eddies formed behind the initial blockages. At the microscopic level, each impact of a quartz grain—possessing a hardness significantly greater than the annealed or work-hardened stainless steel—inflicts a minute amount of plastic deformation. If the impact angle is low, the particle acts as a micro-machine tool, plowing a furrow into the metal surface and pushing a “lip” of material to the sides or the end of the crater. Subsequent impacts by other particles then tear these vulnerable lips away, resulting in mass loss. If the impact is more direct, the energy is dissipated through localized hertzian contact stresses that exceed the yield strength of the alloy, leading to the work-hardening of the surface layer. This work-hardened layer, while initially more resistant, eventually becomes brittle; under the relentless bombardment of sand, micro-cracks propagate along grain boundaries or through the crystalline lattice, leading to the spalling of metallic flakes. This is not a uniform process across the mesh; rather, it is concentrated at the “crossover points” of the weave where the wires are already under residual tensile or compressive stress from the weaving process itself. These crossover points act as stress concentrators, and when the abrasive fluid jet is directed into these crevices, the rate of material removal is accelerated by orders of magnitude compared to the smooth segments of the wire.

The complexity of the damage is further deepened when we account for the electrochemical environment of the oilfield. The reservoir fluids are rarely chemically inert; they often contain brine, $CO_2$, and sometimes $H_2 S$, creating a corrosive medium. The microscopic erosion process continuously strips away the passive chromium oxide ($Cr_2 O_3$) layer that grants stainless steel its corrosion resistance. This creates a synergistic effect known as “erosion-corrosion,” where the mechanical impact facilitates chemical attack and the chemical attack softens the metal surface, making it more susceptible to further mechanical erosion. In the microscopic monologue of the failing wire, we see a “fresh” metal surface being exposed millisecond by millisecond, only to be immediately attacked by chloride ions, which initiate pitting. These pits then serve as the perfect initiation sites for further erosive cutting. Furthermore, the plugging material itself—the sand bridge—is not a static wall. It is a porous, abrasive “grinding wheel” that vibrates under the influence of the turbulent flow. The small-scale oscillations of the bridged particles against the metal wires cause “fretting” damage, a form of wear that occurs at the contact interface between the sand and the metal. This fretting thins the wire diameter slowly but steadily, reducing the structural cross-section and lowering the burst or collapse pressure of the entire screen assembly.

As we peer deeper into the fluid dynamics at the pore scale, the role of the Reynolds number ($Re$) becomes paramount. In an unplugged mesh, the $Re$ is typically low, but as the pore throat narrows to a fraction of its original size, the local $Re$ can spike, leading to the transition to turbulence. This turbulence creates a distribution of impact velocities and angles that defies simple linear modeling. High-fidelity Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) coupled with Discrete Element Modeling (DEM) has shown that the most severe erosion often occurs not at the point of maximum plugging, but in the “shadow zones” immediately downstream of a partial blockage. Here, the flow detaches and forms vortices that trap fine particles, forcing them to strike the back-side of the wire at high frequencies. This “back-side erosion” is particularly insidious because it is hidden from macroscopic inspection. The microscopic damage morphology in these zones often shows a “honeycomb” or “dimpled” appearance, characteristic of high-cycle, low-energy impacts that eventually lead to fatigue failure of the wire. The wire, already thinned by erosion, eventually reaches a point of mechanical instability where the drag forces of the fluid exceed the remaining tensile strength of the metal, leading to the snapping of individual wires—a “wire blowout.” Once a single wire fails, the structural integrity of the entire weave is compromised; the hole rapidly expands as the high-pressure fluid finds a path of least resistance, leading to “hotspotting” and the ultimate failure of the sand control system, which allows formation sand to flood into the production tubing.

To synthesize these observations into a comprehensive understanding of the microscopic damage mechanism, one must recognize the importance of the initial weave geometry and the “surface topography” of the wires. A “smooth” wire is never truly smooth at the micron scale; it contains drawing marks, microscopic ridges, and metallurgical inclusions. These imperfections serve as the primary anchors for the initial deposition of fine particles—the precursors to plugging. If we analyze the interaction between these fines and the metal surface through the lens of DLVO theory (Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek), we see that Van der Waals forces and electrostatic double-layer forces play a critical role in the initial “sticking” of particles. Once the first layer of fines is adsorbed onto the wire, it increases the surface roughness, which in turn increases the coefficient of friction for subsequent, larger particles. This “bio-fouling” like progression of mineral deposition is what eventually bridges the gap. The microscopic damage is thus not an instantaneous event but a temporal evolution of states: from surface adsorption to mechanical bridging, then to hydrodynamic acceleration, then to localized erosive pitting, and finally to structural fatigue and rupture. The study of this progression requires more than just post-mortem SEM analysis; it requires in-situ monitoring of the pressure drop across the mesh, which serves as a macroscopic proxy for the microscopic chaos occurring within the pores. A nonlinear increase in the rate of pressure change is often the “death rattle” of the screen, indicating that the plugging has reached the critical threshold where erosion is now the dominant force.

The scientific analysis must also contend with the “particle-particle interaction” within the high-velocity jet. In a densely packed stream of sand being forced through a plugged pore, the particles do not act independently. They collide with each other, shattering into even smaller, sharper fragments—a process known as comminution. These “newly born” fragments possess fresh, sharp edges that are even more effective at cutting the metal wire than the original rounded reservoir grains. This “autogenous grinding” within the flow stream further accelerates the erosion rate. When we examine the failed wires under a microscope, we often find “embedded” sand fragments that have been driven into the metal surface by the sheer force of the fluid. these embedded particles act as new “teeth” on the wire, further perturbing the flow and creating a secondary level of micro-turbulence. The damage is fractal in nature—large-scale screen failure is composed of thousands of wire failures, which are composed of millions of micro-craters, each formed by the complex dance of fluid, sand, and metal.

To mitigate this, the industry has looked toward surface treatments like nitriding, carburizing, or the application of ceramic coatings to increase the surface hardness. However, at the microscopic level, these coatings introduce their own set of problems. A hard, brittle coating on a ductile stainless steel wire can crack under the mechanical vibration of the flow. Once the coating is breached, the “shadow erosion” mentioned earlier can undercut the coating, leading to large-scale delamination—a phenomenon known as “eggshell” failure. Therefore, the microscopic damage mechanism suggests that the solution lies not just in hardness, but in “toughness”—the ability of the material to absorb the kinetic energy of the sand without undergoing plastic deformation or brittle fracture. This leads us back to the fundamental importance of the weave design itself. By optimizing the pore distribution to be more “uniform” and less “tortuous,” we can theoretically delay the onset of bridging. If the particles can pass through the mesh without forming that initial keystone bridge, the “nozzle effect” is never triggered, and the erosion rate remains within the “design life” of the screen. This conceptual shift—from “stopping all sand” to “managing sand transport”—is the logical conclusion of our microscopic investigation into the failure mechanisms of wire mesh filters.

The microscopic monologue of the failing wire mesh must inevitably turn toward the hidden interplay between metallurgical fatigue and the localized fluid-structure interaction (FSI) that occurs at the scale of a single pore. When I contemplate the structural integrity of a 316L stainless steel wire under the relentless bombardment of formation sand, I am not merely looking at a surface being “sanded down” but rather at a complex arena of high-cycle fatigue and phase transformations induced by mechanical stress. Austenitic stainless steels, while prized for their corrosion resistance, are susceptible to strain-induced martensitic transformation ($SIMT$). As each sand particle strikes the wire, the localized plastic deformation does more than just move metal; it alters the very crystalline structure of the alloy. Under the microscopic lens, we can observe the transition from a relatively ductile face-centered cubic ($fcc$) austenite to a harder, more brittle body-centered tetragonal ($bct$) martensite. This transformation is a double-edged sword; while it initially increases the surface hardness, it creates a significant mismatch in mechanical properties at the grain boundaries. These “hard zones” become the focal points for micro-crack initiation. As the fluid velocity increases due to the aforementioned plugging-nozzle effect, the wire begins to vibrate—a phenomenon known as vortex-induced vibration ($VIV$) at the micro-scale. These high-frequency oscillations, occurring in a medium that is both corrosive and abrasive, drive the propagation of these micro-cracks through the thickness of the wire. This is why we often see “brittle-like” fractures in wires that should theoretically be highly ductile. The failure is not a simple snap; it is the culmination of millions of microscopic “insults” to the metal’s lattice, leading to a state of exhaustion where the wire can no longer dissipate the kinetic energy of the flow.

Furthermore, we must deeply consider the role of the “boundary layer” at the fluid-solid interface within the plugged mesh. In a clean filter, the boundary layer is relatively stable, providing a thin cushion that can actually mitigate some of the impact energy of the finest particles. However, as the pores begin to plug, the flow becomes increasingly turbulent, and the boundary layer is effectively stripped away or “compressed” against the wire surface. This brings the full kinetic energy of the entrained sand into direct contact with the metal. I often think about the Stokes number ($St$) in this context, which is the ratio of the characteristic time of a particle to the characteristic time of the fluid flow. When $St \gg 1$, the particles are essentially “uncoupled” from the fluid streamlines; they do not follow the graceful curves of the water or oil as it navigates the weave but instead travel in straight, ballistic trajectories that slam into the crossover points of the mesh. Conversely, when $St \ll 1$, the particles are small enough to be carried by the fluid, but even these “fines” contribute to a different kind of damage: “silt erosion.” This is a more insidious, polishing-like wear that thins the wire diameter without the dramatic cratering seen with larger grains. Over thousands of hours of production, this diameter reduction—combined with the chemical leaching of chromium and nickel in the presence of acidic reservoir fluids—significantly reduces the moment of inertia of the wire cross-section. The result is a dramatic increase in the bending stresses at the weave intersections, leading to “fatigue-corrosion” failures that often manifest as the systematic unraveling of the mesh.

The complexity of the damage is amplified when we introduce the concept of “comminution” or the secondary breakage of particles within the high-velocity jets. Imagine a quartz grain that is slightly too large to pass through a partially plugged pore. It becomes lodged, but under the immense pressure differential—sometimes exceeding several megapascals—the particle itself is crushed. This creates a shower of fresh, angular fragments with “virgin” surfaces that are incredibly sharp. These fragments are then accelerated through the remaining gaps in the plug, acting like microscopic shrapnel. This secondary erosion is often more severe than the primary erosion caused by the original reservoir sand because the fragments are more angular and have a higher surface-area-to-mass ratio, allowing them to be accelerated to even higher velocities. When we analyze the surface topography of a failed screen, we often find a “multi-modal” damage pattern: large, deep craters from the primary impacts, and a dense field of micro-scratches and pits from the secondary fragments. This suggests that the plugging of the screen doesn’t just increase the number of impacts; it fundamentally changes the nature of the abrasive medium, transforming a relatively rounded sand into a sharp, crushed grit that is far more lethal to the metallic substrate.

As we transition our thinking from the mechanical to the chemical, we must acknowledge the “galvanic cells” that are created within the plugged pore itself. The sand bridge is not just a physical barrier; it creates a “crevice” where the fluid chemistry can diverge significantly from the bulk fluid in the wellbore. Inside the plug, the fluid can become stagnant, leading to oxygen depletion and the buildup of acidic byproducts or concentrated chlorides. This sets up a “crevice corrosion” cell between the metal surface inside the plug (the anode) and the exposed metal surface outside the plug (the cathode). The erosion process then acts as a continuous “depassivator,” scraping away any protective scale or oxide film that the metal tries to form in this harsh environment. This synergy—where erosion accelerates corrosion by removing the passive layer, and corrosion accelerates erosion by softening the metal and widening the micro-cracks—is the “death spiral” of the sand control screen. It is a process where the physics of the fluid and the chemistry of the reservoir conspire to exploit every microscopic weakness in the weave. Scientific modeling of this process requires a multi-physics approach, coupling the Navier-Stokes equations for the fluid, the Discrete Element Method ($DEM$) for the particles, and electrochemical kinetic models for the metal dissolution. Only by integrating these disparate fields can we begin to predict the “time to failure” with any degree of accuracy.

The industrial implication of this research points toward a desperate need for “sacrificial” or “gradient” filter designs. If we know that the initial plugging is the trigger for the destructive erosion, perhaps the filter should be designed to “shed” its first layer of plugs, or to have a pore structure that expands slightly under pressure to allow the “keystone” bridges to collapse before they can trigger the nozzle effect. This brings us to the fascinating area of “shape memory” alloys or flexible weaves that can dynamically respond to the plugging state. However, the current reality remains rooted in rigid, high-strength alloys where the battle is won or lost at the micron scale. Looking at the cross-section of a failed wire under a Scanning Electron Microscope ($SEM$), the story is written in the “striations” and “dimples”—a narrative of a material that fought a valiant but losing battle against a fluid that it was meant to tame but which eventually became its destroyer. The microscopic damage mechanism is, therefore, a testament to the fact that in the world of high-pressure fluid dynamics, there is no such thing as a “static” filter; there is only a material in a state of slow, measured decay, and our job as scientists is to understand the tempo of that decay well enough to ensure the well survives its economic life.