Ultra-Resilient Dual-Layer Gravel Pack Screen

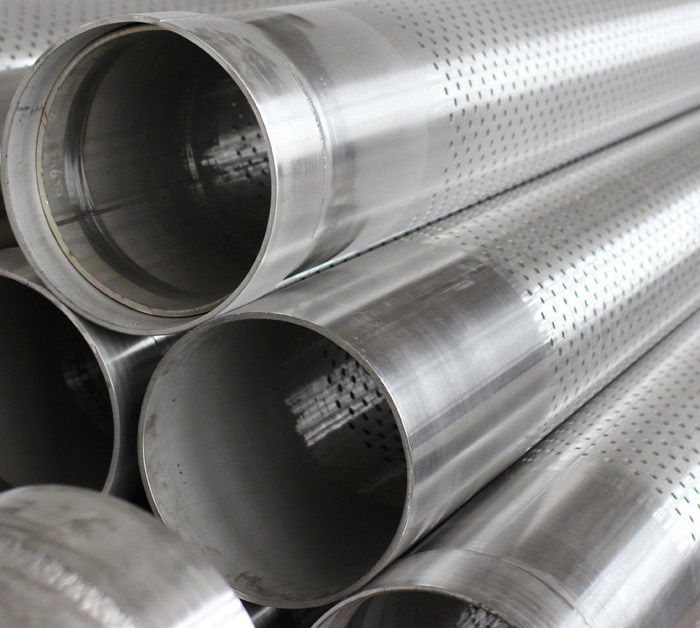

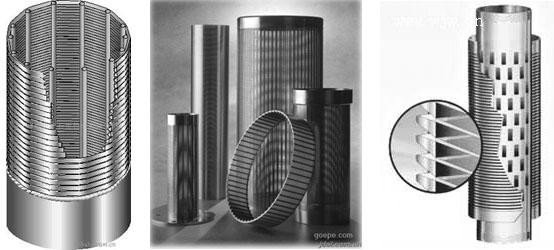

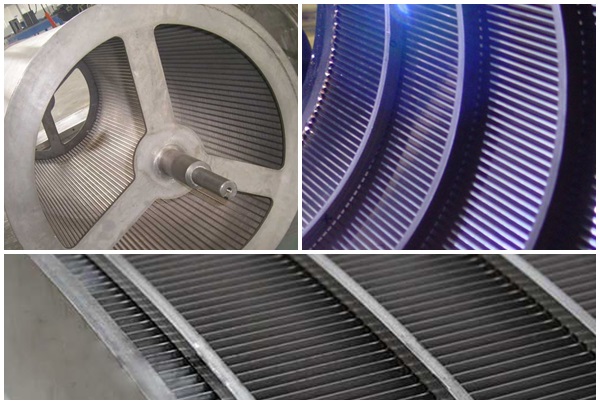

December 10, 2025When we step into the realm of subsurface fluid dynamics and sand management, we aren’t just looking at plumbing; we are looking at the critical interface between a multi-million dollar asset (the reservoir) and the surface. The transition from traditional perforated pipes or bridge-slot screens to V-shaped wire profiles—often termed “continuous slot” or “Wedge Wire”—represents a fundamental evolution in mechanical filtration.

To truly understand why the V-profile is superior, we have to look past the surface-level marketing and dive into the physics of flow, the geometry of particle bridging, and the structural integrity of materials under extreme hydrostatic pressure.

The Inner Monologue: Rethinking the Filter

I’m thinking about the way a grain of sand—let’s say it’s a 150-micron quartz particle—approaches a barrier. In a traditional perforated pipe, that particle sees a wall with holes. If it hits the edge of a hole, it stops. If two particles hit at once, they bridge. But in a V-shaped profile, the geometry changes the rules of engagement. I need to explore how the widening gap inside the wire profile prevents the most common cause of well failure: plugging. It’s not just about stopping sand; it’s about letting the fluid through without restriction. If the velocity is too high, the sand acts like a liquid sandpaper, eroding the very screen meant to stop it. This is where the Total Open Area comes in. I should compare the flow regimes—laminar versus turbulent—and how the V-shape maintains the former. Then there is the manufacturing aspect. A bridge slot is a mechanical deformation of a pipe, creating stress points. A V-wire screen is an engineered assembly. I need to contrast the ‘skin factor’ of these two methods. How does the pressure drop across the screen affect the long-term productivity index of the well?

1. Geometric Fluid Dynamics: The “Self-Cleaning” Mechanism

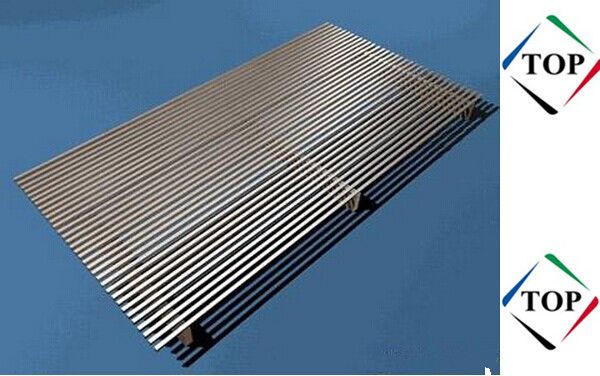

The primary advantage of the V-shaped wire is its inward-widening slot. Traditional perforated pipes or slotted liners utilize parallel-walled or even slightly irregular apertures.

The Failure of Parallel Slots

In a parallel slot (found in milled or perforated pipes), a particle that is slightly larger than the slot width becomes wedged. Because the walls of the slot are parallel, the particle is held by friction along its entire depth. This creates a “seed” for a filter cake to build up. Once one particle is stuck, smaller particles (fines) begin to accumulate behind it. This is the definition of mechanical plugging.

The V-Wire Solution

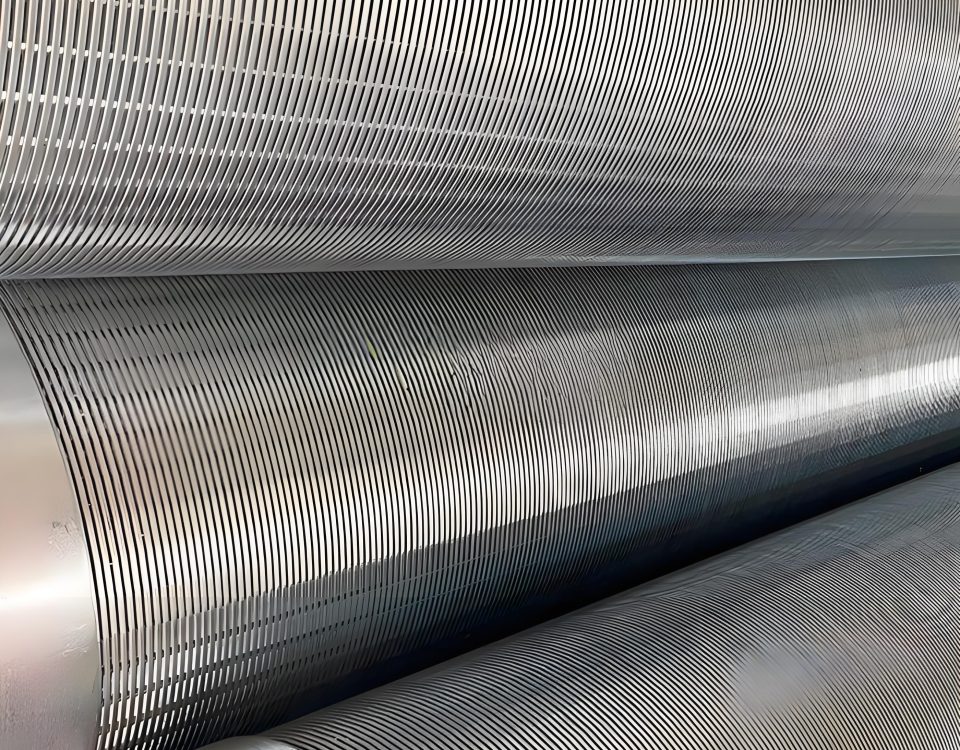

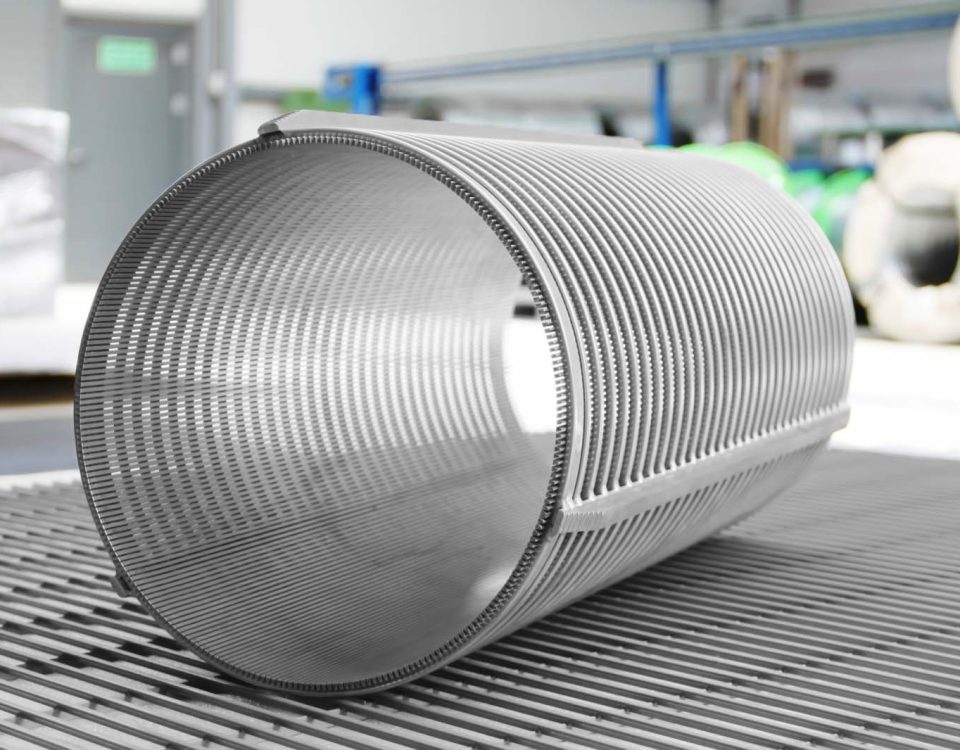

The V-shaped wire is oriented with the “point” of the V facing inward and the flat base facing outward (or vice versa depending on the flow direction, but typically for sand control, the narrowest point is the entry).

-

Two-Point Contact: A sand grain can only touch the screen at two points on the outer edges of the V-wire.

-

Instant Release: Because the slot widens inwardly, any particle that manages to pass the initial opening will necessarily be smaller than the space it is moving into. There is no further constriction to hold it.

-

Internal Turbulence: The widening gap creates a micro-expansion zone for the fluid, which helps flush fines through the screen and into the production stream, where they can be managed by surface separators, rather than clogging the wellbore.

2. Analysis of Total Open Area (TOA) and Flow Velocity

In reservoir engineering, velocity is the enemy of stability. High-velocity fluid creates “hot spots” where erosion is accelerated.

The Constriction Effect

Perforated pipes are limited by the structural integrity of the base pipe. You cannot drill too many holes without making the pipe collapse under its own weight or the pressure of the formation. Consequently, the Total Open Area (TOA) of a perforated liner is usually between 3% and 6%.

When 100% of the reservoir’s flow is forced through only 5% of the pipe’s surface area, the fluid must accelerate. This is basic Darcy’s Law and the principle of continuity. High entrance velocity leads to:

-

Erosion: Sand particles hitting the steel at high speeds “sandblast” the metal.

-

Turbulence: High velocity induces Reynolds numbers that move out of the laminar flow regime, increasing the pressure drop ($ΔP$).

The V-Wire Efficiency

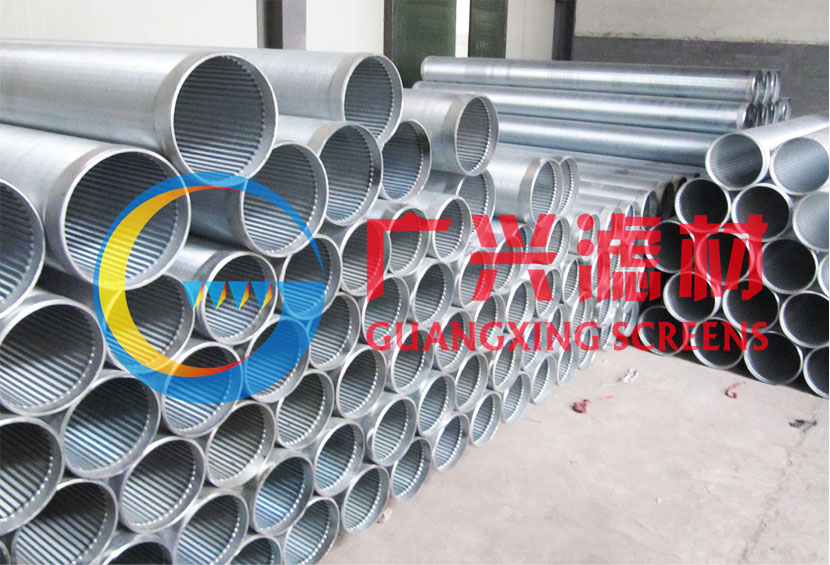

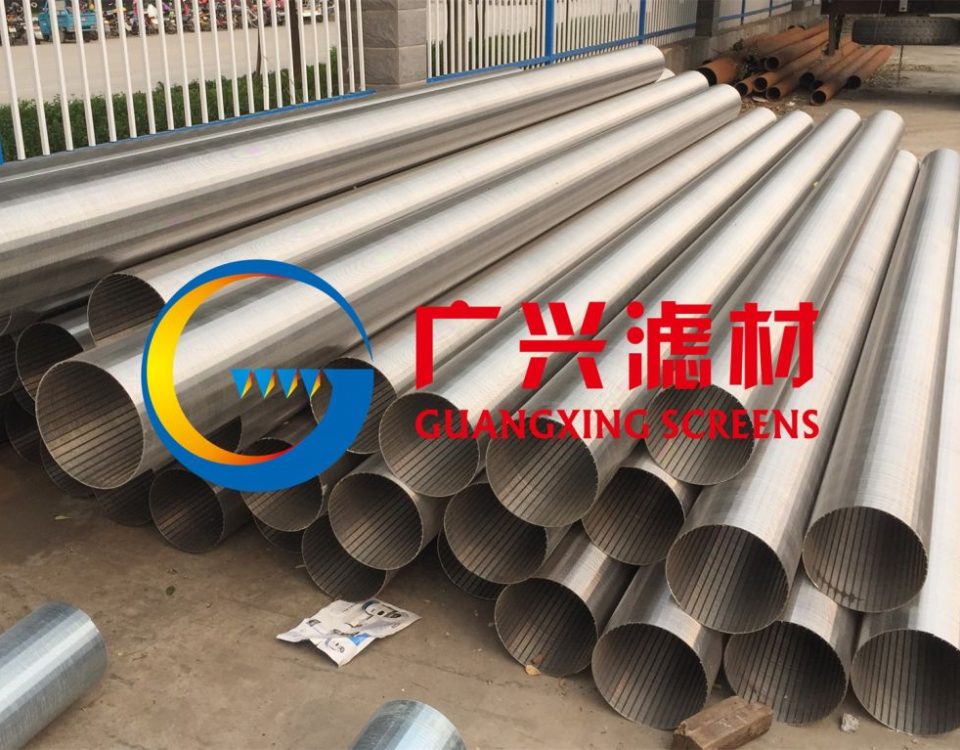

Because the V-wire is wrapped continuously around support rods, the TOA can be as high as 25% to 40%.

| Performance Metric | Perforated Pipe | Bridge Slot Screen | V-Wire (Continuous Slot) |

| Typical Open Area | 3% – 7% | 6% – 10% | 15% – 35% |

| Entrance Velocity | Very High | High | Low/Uniform |

| Flow Profile | Non-uniform (Point source) | Semi-uniform | Uniform (Line source) |

| Plugging Tendency | High | Medium | Very Low |

| Skin Factor ($S$) | Higher ($+2$ to $+5$) | Moderate | Near Zero |

By providing a massive open area, the V-wire screen allows the fluid to enter the pipe at a much lower velocity. This preserves the “laminar” flow, keeping the sand particles outside the screen stable and preventing the “liquefaction” of the sand pack.

3. Structural Integrity and Stress Distribution

The way we manufacture these profiles determines how they handle the crushing forces of a deep-sea or high-pressure well.

-

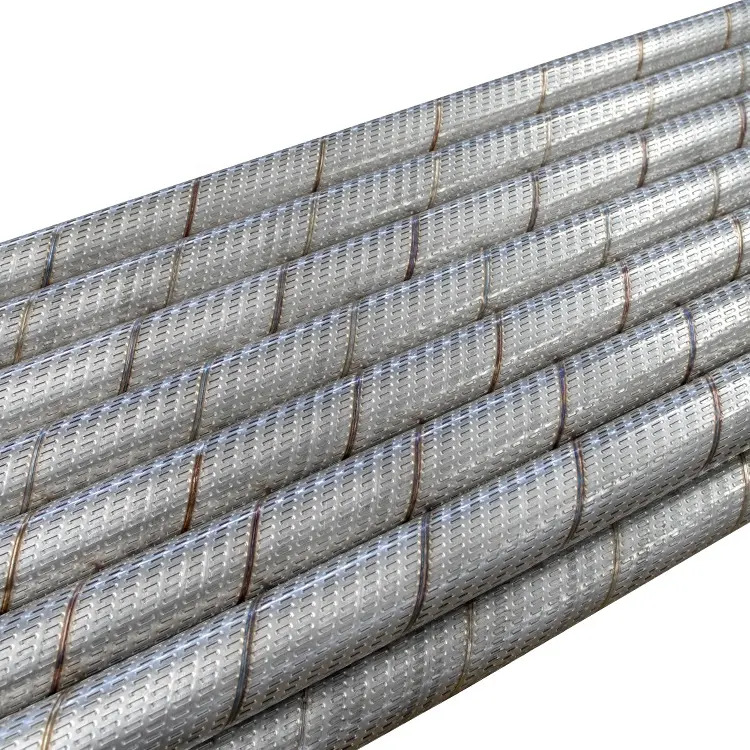

Bridge Slot: This is made by punching a hole and pushing the metal out to create a “bridge.” This process creates massive Residual Stress. The corners of the bridge are prone to stress corrosion cracking (SCC) because the molecular structure of the steel has been torn and stretched.

-

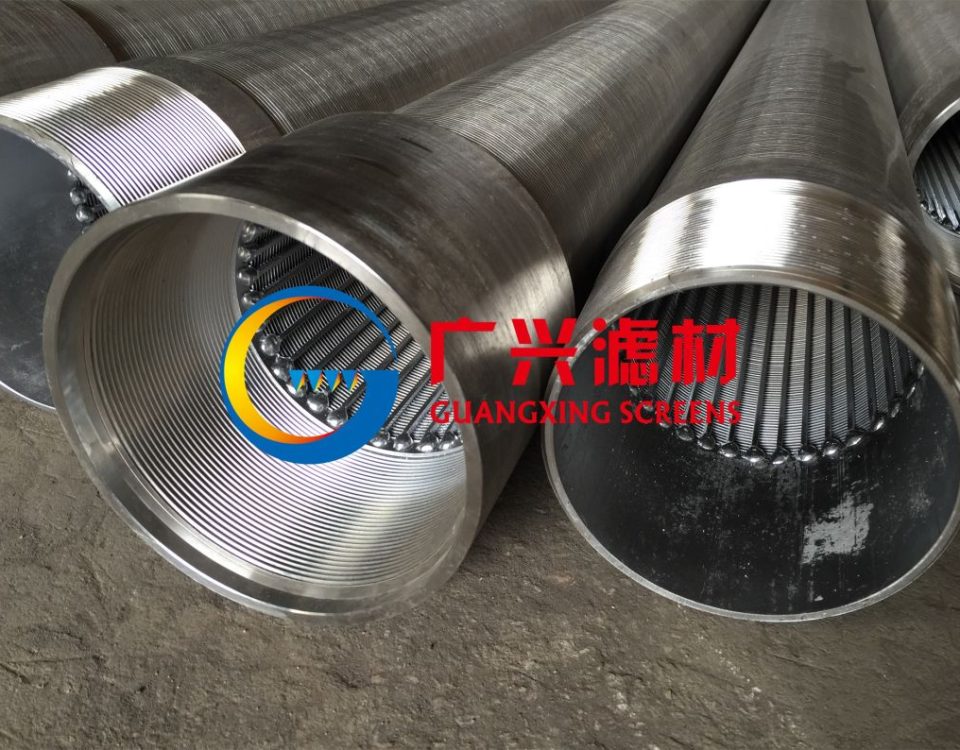

V-Wire Screens: These are manufactured through a sophisticated resistance-welding process. A V-shaped wire is cold-rolled—which actually increases the material’s yield strength through work hardening—and then wrapped around longitudinal support rods. Every single intersection is welded.

This creates a truss-like architecture. The load is distributed across the entire “cage” of the screen rather than being concentrated at the edges of a punched hole.

Resistance to Collapse

In deep wells, the formation can “creep” or settle, applying a radial load on the screen.

-

Perforated Pipe can fail by buckling at the hole patterns.

-

V-Wire Screens act like a cylindrical arch. The V-shape of the wire provides a larger “base” to resist the inward pressure of the formation.

4. Precision Engineering: The Slot Tolerance Factor

When managing a reservoir with a specific grain size distribution (GSD), precision is everything. If your GSD analysis says you need to stop particles larger than 150 microns, but your screen has a tolerance of $\pm 50$ microns, you are going to have a sand failure.

-

Manufacturing Tolerance: Bridge slots are mechanically punched. The tools wear down, and the spring-back of the metal varies. It is very difficult to maintain a consistent gap.

-

V-Wire Precision: Modern V-wire winding machines use laser-controlled gap adjustment. We can achieve a consistent slot width with a tolerance of $\pm 0.01\text{ mm}$.

This level of precision allows for the design of “Stand-alone Screens” (SAS). In many completions, we don’t want to use a gravel pack (pumping specialized sand outside the screen). We want the screen to be the only barrier. If the slot isn’t perfectly consistent, the “fines” will leak through the largest gaps, eventually leading to a total breach of the sand control system.

5. Skin Factor and Productivity Index (PI)

The ultimate goal of any completion is to maximize the Productivity Index (PI). PI is defined as the flow rate divided by the drawdown ($PI = Q / ΔP$).

A perforated pipe creates a “point-source” flow. The oil must travel through the reservoir, converge at the tiny hole, and squeeze through. This convergence creates a localized pressure drop known as the Skin Effect.

The V-wire screen, with its continuous slot, creates a “surface-source” flow. The reservoir fluid moves linearly into the screen.

-

Lower Drawdown: Because there is less resistance at the screen, you can produce the same amount of oil with less “pull” on the reservoir.

-

Preventing Water Coning: High drawdown often pulls bottom-water or gas-caps toward the wellbore prematurely. By minimizing the pressure drop across the V-wire screen, we extend the life of the well by keeping the fluid interfaces stable.

6. Economic Lifecycle Analysis

While the initial cost of a V-wire screen is higher than a perforated pipe (due to the complex welding and cold-rolling of the wire), the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is significantly lower.

-

Workover Costs: A “sanded-out” well requires a workover that can cost millions in rig time. V-wire screens drastically reduce the probability of this event.

-

Pump Life: In wells using Electrical Submersible Pumps (ESPs), even a small amount of sand passing through a bridge-slot screen will destroy the pump’s impellers. The superior filtration of V-wire protects these expensive downstream assets.

-

Well Stimulation: V-wire screens are much easier to clean. If the well becomes scaled or fouled, the inward-widening slots allow for more effective acid washing or “jetting” compared to the convoluted paths of a bridge slot.

Conclusion: The Technical Verdict

The transition to V-shaped wire profiles is a move from “crude mechanical barriers” to “engineered fluid interfaces.” By optimizing the cross-sectional geometry, we address the three pillars of completion success: Sand Retention, Flow Efficiency, and Mechanical Longevity.

-

The V-shape prevents plugging through its expanding geometry.

-

The Continuous Slot maximizes open area and minimizes entrance velocity.

-

The All-Welded Construction provides the structural integrity needed for the world’s most demanding high-pressure/high-temperature (HPHT) environments.

In the modern oilfield, where “cheap” often leads to “failed,” the V-wire profile stands as the gold standard for sustainable, high-rate production.

Would you like me to generate a specific technical data sheet comparing different wire gauges (e.g., 60-wire vs. 90-wire) for specific formation collapse pressures?