The Profound Influence of Manufacturing Processes on the Microstructure and Performance of Stainless Steel Well Screens

September 6, 2025

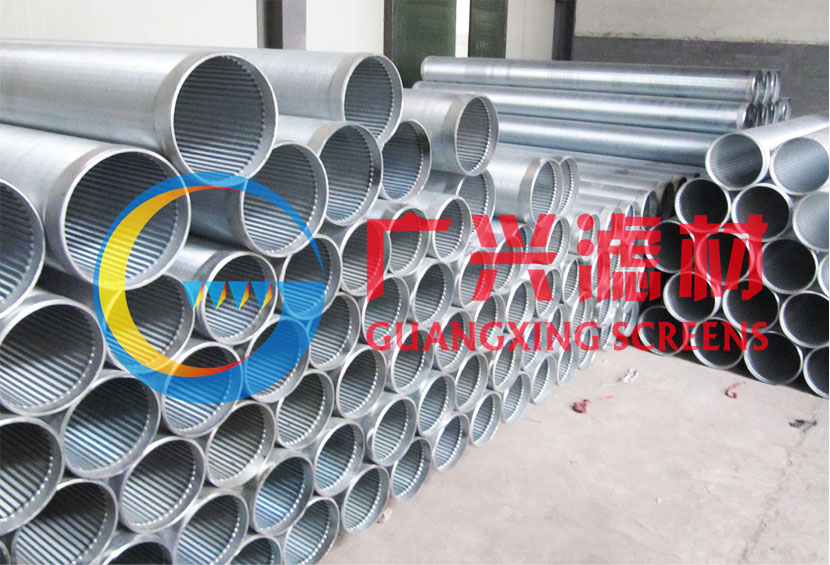

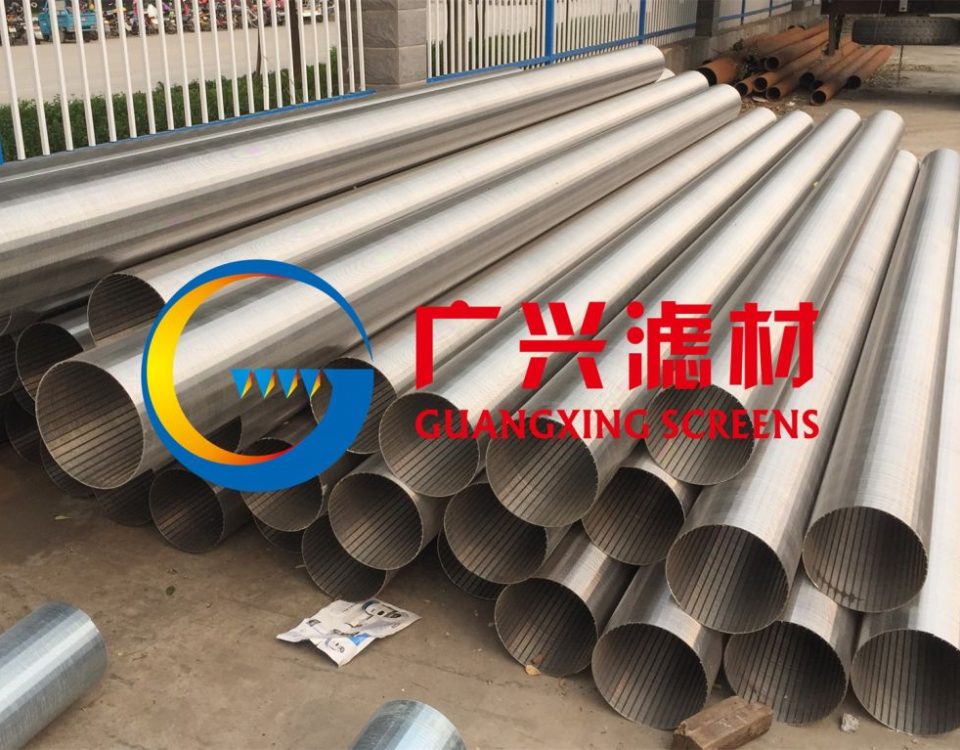

The Essential Guide to Water Well Screen Filter Pipe

September 14, 2025The Influence of Manufacturing Processes on the Microstructure and Performance of Stainless Steel Well Screens

The selection of a stainless steel alloy (e.g., 304, 316L, 2205) for a well screen is merely the first step in defining its potential performance. While the nominal chemical composition of the alloy sets the baseline for properties like corrosion resistance and phase stability, it is the manufacturing process that ultimately dictates the real-world microstructure, mechanical properties, and long-term durability of the final screen. Every stage of transformation, from molten metal to a precision-engineered filtration device, imparts specific and often profound changes to the material’s internal architecture—its microstructure. Understanding this intimate relationship between process, structure, and properties is paramount for engineers, hydrogeologists, and well designers to specify and utilize these critical components effectively.

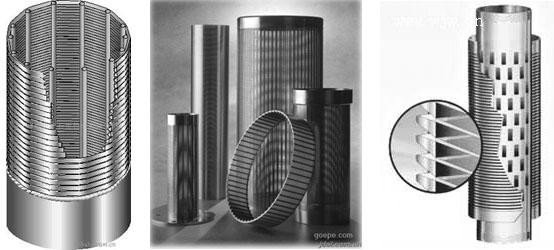

This analysis will deconstruct the major manufacturing pathways for stainless steel well screens—focusing on the dominant methods for creating slotted pipes and wire-wrapped screens—and elucidate how each operation alters the microstructure and, by extension, the key performance metrics of collapse strength, corrosion resistance, fatigue life, and slot integrity.

1. Foundational Concepts: The Link Between Process, Structure, and Properties

Before delving into specific processes, it is crucial to establish the fundamental materials science principle: Processing → Structure → Properties.

-

Processing: This encompasses all manufacturing steps: melting, casting, hot and cold working, heat treatment, machining, and finishing.

-

Structure: This refers to the material’s internal architecture at various scales:

-

Atomic Scale: Crystal structure (FCC Austenite, BCC Ferrite, etc.), chemical composition homogeneity, presence of secondary phases (carbides, nitrides).

-

Microscopic Scale: Grain size, grain boundary character, phase distribution, dislocation density, and texture (preferred grain orientation).

-

Macroscopic Scale: Voids, inclusions, residual stresses, and surface finish.

-

-

Properties: The resulting mechanical (yield strength, hardness, toughness), chemical (corrosion resistance), and physical (magnetic permeability) behaviors.

A change in the processing route inevitably alters the structure, which directly controls the properties. The goal of optimized manufacturing is to guide these structural changes to achieve the most desirable set of properties for the application.

2. Raw Material Production: The Genesis of Microstructure

The journey begins with the production of the raw stainless steel, which forms the pipe or wire used later.

A. Melting and Casting:

Stainless steel is typically produced in Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF) followed by refining in an Argon Oxygen Decarburization (AOD) vessel. This process precisely controls the carbon content and minimizes impurities. The molten steel is then continuously cast into slabs or billets.

-

Microstructural Impact: The solidification process creates a coarse, dendritic (tree-like) microstructure. Chemical segregation occurs, where alloying elements like chromium and molybdenum are not uniformly distributed but are concentrated in the spaces between the dendritic arms. This heterogeneity can create localized weak spots for corrosion initiation if not addressed later.

-

Performance Impact: A coarse, segregated cast structure has lower mechanical strength and inferior toughness. It is entirely unsuitable for direct fabrication into a well screen. This necessitates subsequent mechanical processing to refine the structure.

B. Hot Working (Hot Rolling/Forging):

The cast billets are reheated to high temperatures (typically above 1000°C for austenitic steels) where the steel is in a soft, ductile austenitic phase. They are then rolled or forged into smaller dimensions, such as bars or the initial hollows for pipes.

-

Microstructural Impact: This is a process of dynamic recrystallization. The coarse cast grains are deformed and broken up. New, finer, and equiaxed (uniform in all directions) grains nucleate and grow. This significantly refines the grain size. Hot working also helps to reduce (but not eliminate) the chemical segregation from casting by promoting diffusion.

-

Performance Impact:

-

Strength and Toughness: The Hall-Petch relationship states that yield strength increases inversely with the square root of the grain diameter. Grain refinement is the only mechanism that simultaneously increases both strength and toughness. A fine-grained, hot-worked structure is stronger and more resistant to impact and fracture than the coarse cast structure.

-

Corrosion Resistance: A finer, more homogeneous grain structure promotes the formation of a more uniform and protective passive chromium oxide layer (Cr₂O₃) on the surface.

-

3. Pipe and Wire Manufacturing: Setting the Stage

The hot-worked product is then further processed into the forms needed for screens: seamless pipe for slotted screens and rod for wire-wrap.

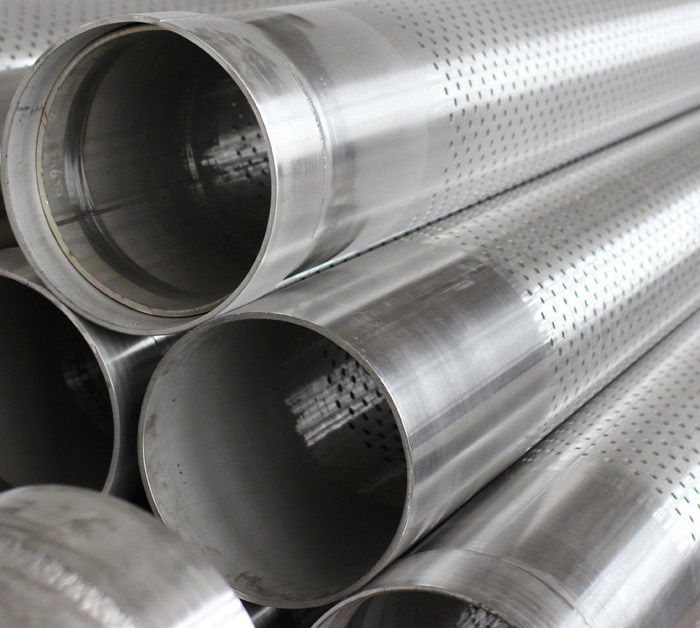

A. Seamless Pipe Production (e.g., Mannesmann plug mill process):

A hot-worked bar is pierced to create a hollow shell, which is then elongated and rolled to the final diameter and wall thickness.

-

Microstructural Impact: The process involves further hot working, further refining the grain structure. The final microstructure is a fine-grained austenite (in 300-series steels). The pipe may be solution annealed and quenched thereafter to dissolve any carbides that may have precipitated during slow cooling from hot-working temperatures.

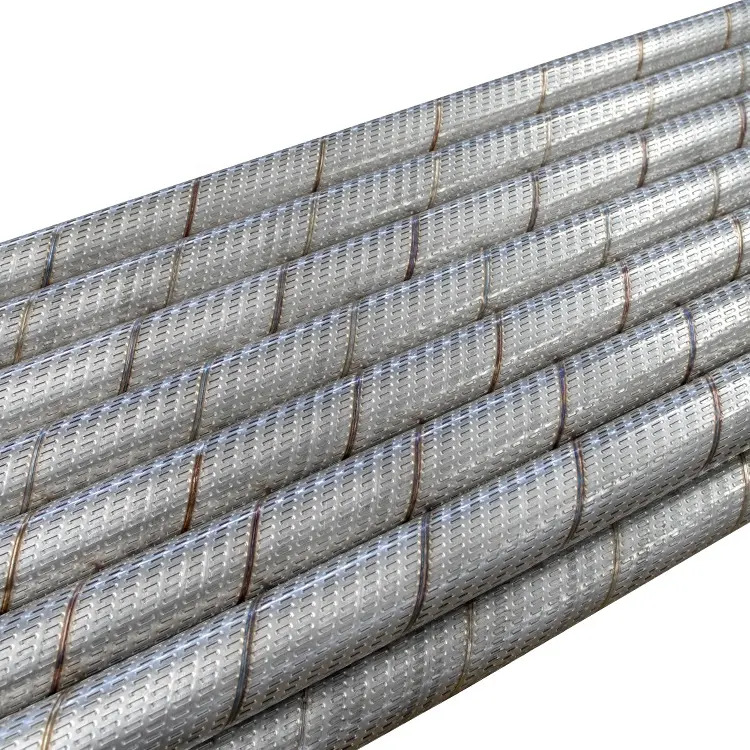

B. Welded Pipe Production (e.g., continuous weld):

A strip of steel (skelp) is passed through forming rolls that bend it into a cylindrical shape. The edges are then heated and forged together to form a weld.

-

Microstructural Impact:

-

Base Metal: The strip itself is typically cold-rolled and annealed, giving it a fine, recrystallized grain structure.

-

Weld Zone: The welding process creates a Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ). The microstructure in the HAZ is altered by the intense heat:

-

Precipitation: In unstabilized grades like 304 or 316, exposure to temperatures in the range of 450-850°C can cause chromium carbide precipitation (sensitization) at grain boundaries. This depletes the surrounding matrix of chromium, making these zones highly susceptible to intergranular corrosion.

-

Grain Growth: Areas adjacent to the weld can experience significant grain growth, reducing strength and toughness.

-

-

Performance Impact: The weld seam can be a potential weak point. If the pipe is not subsequently fully solution annealed and quenched to re-dissolve the carbides, the HAZ becomes a prime site for corrosive attack, which can lead to premature failure under load. For critical applications, seamless pipe or pipes made from “L” grades (e.g., 316L, with ultra-low carbon) are preferred to mitigate this risk.

-

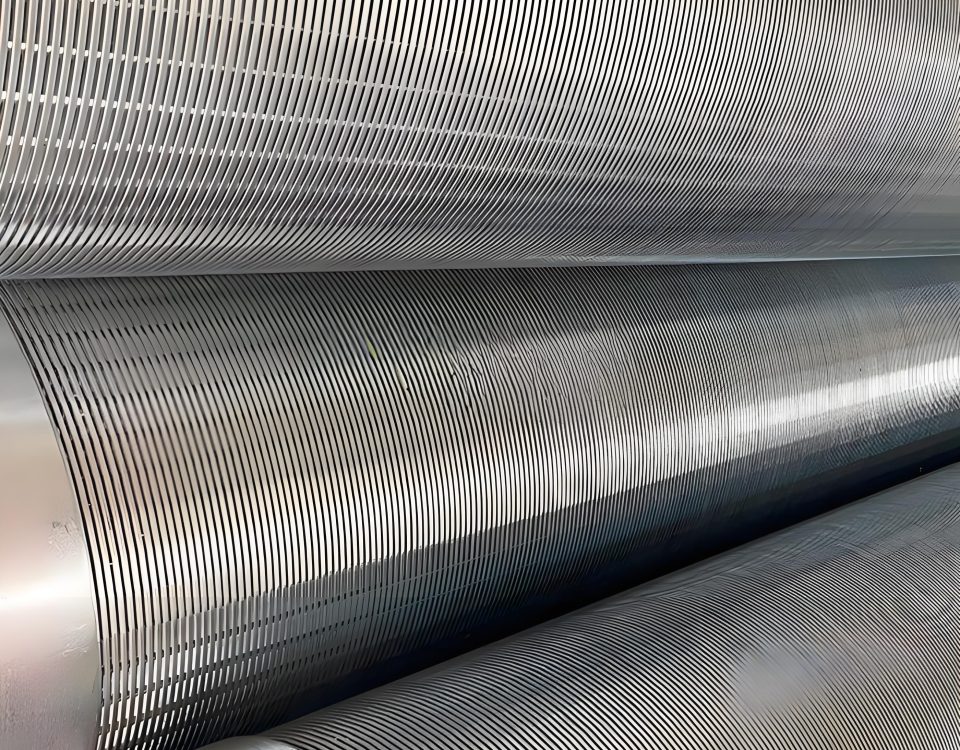

C. Wire Drawing for Wire-Wrap Screens:

Rod is pulled through a series of progressively smaller dies to reduce its diameter to the precise gauge required for the wrap wire.

-

Microstructural Impact: Wire drawing is a severe form of cold working. It introduces a massive number of dislocations into the crystal structure. The grains, which were initially equiaxed, become elongated in the direction of drawing. This creates a highly anisotropic microstructure (properties differ with direction).

-

Performance Impact:

-

Strength: Cold work drastically increases yield and tensile strength through strain hardening (work hardening). The yield strength of a heavily drawn 316 wire can be more than double that of its annealed counterpart.

-

Ductility: The trade-off is a severe reduction in ductility and toughness. The wire becomes harder but more brittle.

-

Residual Stress: The process introduces significant residual tensile stresses at the surface, which can be detrimental to corrosion and fatigue performance if not relieved.

-

4. Screen Fabrication: The Most Critical Phase

This is where the pipe or wire is transformed into a functional screen, and where the most dramatic microstructural changes occur.

A. Slotting Processes (Punching, Laser Cutting, Waterjet Cutting)

-

Punching/Stamping: A hardened tool punches the slot pattern through the pipe wall.

-

Microstructural Impact: This is an extreme cold-working operation localized to the slot perimeter. The material at the edge of the slot is plastically deformed to a massive degree, creating a work-hardened zone with very high dislocation density. The grain structure is severely distorted. The process also introduces residual stresses—typically compressive at the surface but with tensile stresses just beneath.

-

Performance Impact:

-

Strength: The slot edges become very hard and wear-resistant, which is beneficial for abrasion resistance.

-

Corrosion: The high residual stresses and disrupted passive layer in the work-hardened zone can make these areas more susceptible to Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) and pitting corrosion, especially in environments containing chlorides or hydrogen sulfide. The rough, micro-cracked surface left by punching provides ideal initiation sites for pits.

-

Fatigue: The combination of a geometric stress concentrator (the slot) and residual tensile stresses significantly reduces the fatigue strength of the screen. Cyclic loading from pump operation or water hammer can initiate fatigue cracks at the slot roots.

-

-

-

Laser Cutting: A high-power laser beam melts and vaporizes the metal to form the slot.

-

Microstructural Impact: The intense, localized heat input creates a new HAZ along the cut edge. The sequence of microstructures is:

-

Fusion Zone: The very edge where metal was molten and rapidly solidified, forming a cast-like structure of fine dendrites.

-

Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ): Adjacent to the fusion zone, where the material was heated below its melting point but high enough to alter its structure. This can include:

-

Grain growth.

-

Potential carbide precipitation in the sensitization temperature range.

-

Formation of a heat tint—a thick, non-protective oxide layer (often blue or brown) that is depleted in chromium.

-

-

-

Performance Impact:

-

Precision: Produces a much cleaner, more precise slot with a better surface finish than punching.

-

Corrosion: The heat tint and any sensitization in the HAZ are severe vulnerabilities to pitting and crevice corrosion. For this reason, high-quality laser-cut screens must undergo post-cut cleaning (pickling/passivation) to remove the heat tint and restore the passive layer. Electropolishing is an excellent option as it smoothes the surface and leaves it in a highly corrosion-resistant state.

-

Residual Stress: The process induces significant thermal stresses, but they are generally different in character from the mechanical stresses from punching.

-

-

-

Abrasive Waterjet Cutting: Uses a high-pressure stream of water mixed with abrasive garnet to erode the material.

-

Microstructural Impact: This is a cold cutting process. It involves minimal heat input, so there is no HAZ, no phase transformations, and no thermal distortions.

-

Performance Impact:

-

No HAZ: The base material’s microstructure right up to the slot edge remains unchanged. This is a major advantage for corrosion resistance.

-

Surface Finish: The cut edge has a matte, rough finish which, while free of thermal damage, can still be a site for particle adhesion and crevice initiation. Post-cut passivation is still recommended.

-

Residual Stress: Introduces minimal new residual stress, mostly mechanical in nature from the abrasive impact.

-

-

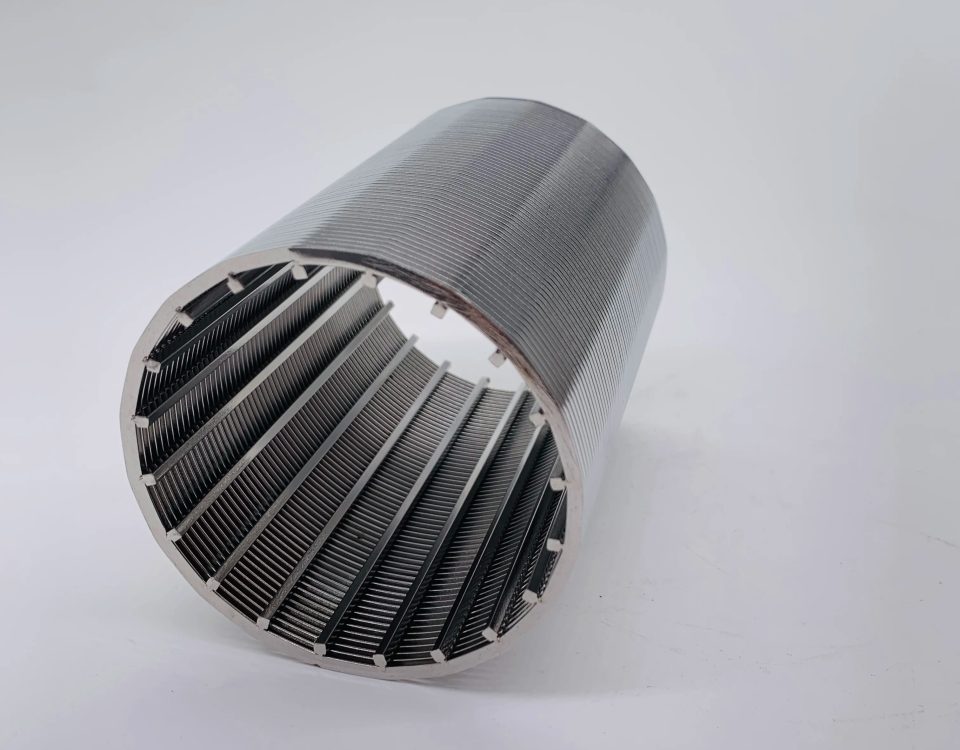

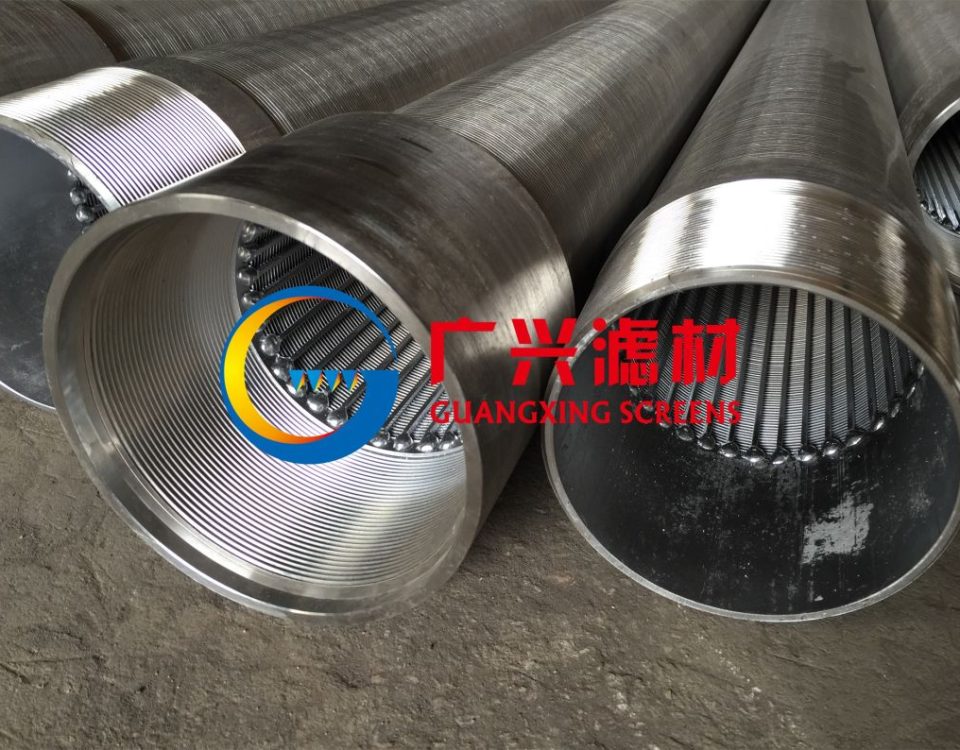

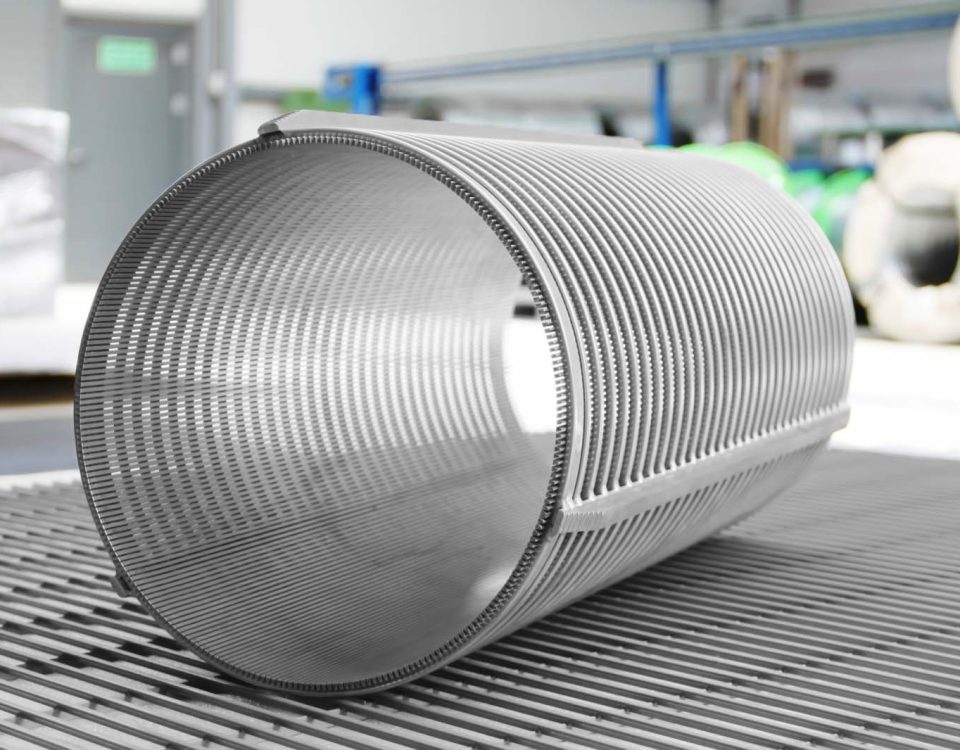

B. Wire-Wrapping and Welding

The drawn wire is helically wrapped around a supporting array of longitudinal rods or a perforated base pipe and welded at each contact point.

-

Microstructural Impact (Weld Points): Each spot weld creates a tiny, localized fusion zone and HAZ. The same risks of sensitization, grain growth, and heat tint formation apply here. The cumulative effect of thousands of weld points can be significant for the overall screen performance.

-

Performance Impact:

-

The base pipe provides the primary structural strength, while the wire wrap defines the slot size.

-

The main corrosion risk is at each weld nugget. Inadequate welding practices or a lack of post-fabrication cleaning can make these points the Achilles’ heel of the entire assembly, leading to localized corrosion and potential unraveling of the wire.

-

5. Finishing Processes: Defining the Surface State

A. Heat Treatment (Annealing):

Performed to relieve stresses, soften cold-worked material, or dissolve precipitated carbides.

-

Solution Annealing & Quenching: The screen is heated to around 1050-1100°C (for 316), held to dissolve all carbides into solid solution, then rapidly quenched in water.

-

Microstructural Impact: Resets the microstructure. Creates a fully austenitic, equiaxed, and recrystallized grain structure with carbides dissolved and no cold work. Eliminates virtually all residual stresses.

-

Performance Impact:

-

Corrosion Resistance: Maximized. Completely eliminates sensitization and provides the best possible resistance to pitting and SCC.

-

Strength: Returns the material to its soft, ductile, annealed state with low yield strength. This can be detrimental to collapse strength. Therefore, solution annealing is often done before final cold-forming steps (like slotting) if high collapse strength is required.

-

-

-

Stress Relieving: Performed at lower temperatures (e.g., ~400-500°C) to reduce internal residual stresses without significantly altering the grain structure or strength.

-

Microstructural Impact: Allows dislocations to rearrange and annihilate, reducing stress.

-

Performance Impact: Improves resistance to SCC and dimensional stability without a major loss of strength gained from cold working.

-

B. Pickling and Passivation:

Chemical treatments critical for corrosion performance.

-

Pickling: Uses a mixture of nitric and hydrofluoric acid to remove surface contamination, scale, and heat tint (the chromium-depleted layer).

-

Passivation: Uses nitric acid (or sometimes citric acid) to promote the rapid formation of a new, continuous, and protective chromium oxide layer on the freshly exposed surface.

-

Microstructural Impact: These processes do not change the bulk microstructure but are absolutely vital for restoring the surface microstructure’s corrosion integrity after thermal processes like welding or laser cutting.

C. Electropolishing:

An electrochemical process that removes a thin layer of surface material.

-

Microstructural Impact: It preferentially removes microscopic peaks, leaving an ultra-smooth surface. It also removes the work-hardened, disturbed surface layer left by mechanical processes.

-

Performance Impact:

-

Corrosion Resistance: dramatically improved by providing a smooth surface with fewer sites for pit initiation and by enriching the surface chromium content.

-

Cleanability: The smooth surface prevents bacterial adhesion and makes the screen easier to clean and rehabilitate.

-

Synthesis: Performance Implications of the Manufacturing Pathway

The chosen manufacturing sequence creates a final product with a specific structural signature:

-

High Collapse Strength Pathway: This requires a heavily cold-worked microstructure.

-

Process: Cold-drawing of pipe + cold slotting (punching) + maybe low-T stress relief.

-

Structure: High dislocation density, elongated grains, high residual stress.

-

Trade-off: Superior mechanical strength but reduced ductility and potentially lower corrosion resistance due to the stressed, disturbed surface.

-

-

High Corrosion Resistance Pathway: This requires a recrystallized, stress-free, and homogeneous microstructure with a perfect surface.

-

Process: Solution annealed pipe + laser/waterjet cutting + thorough pickling/passivation/electropolishing.

-

Structure: Equiaxed grains, dissolved carbides, minimal residual stress, pristine surface.

-

Trade-off: Optimal corrosion performance but lower mechanical strength, relying on thicker walls to achieve required collapse ratings.

-